Writers@Work: Setting Your Story in Another Country

March 9, 2021

Note From Rochelle

Dear Writers,

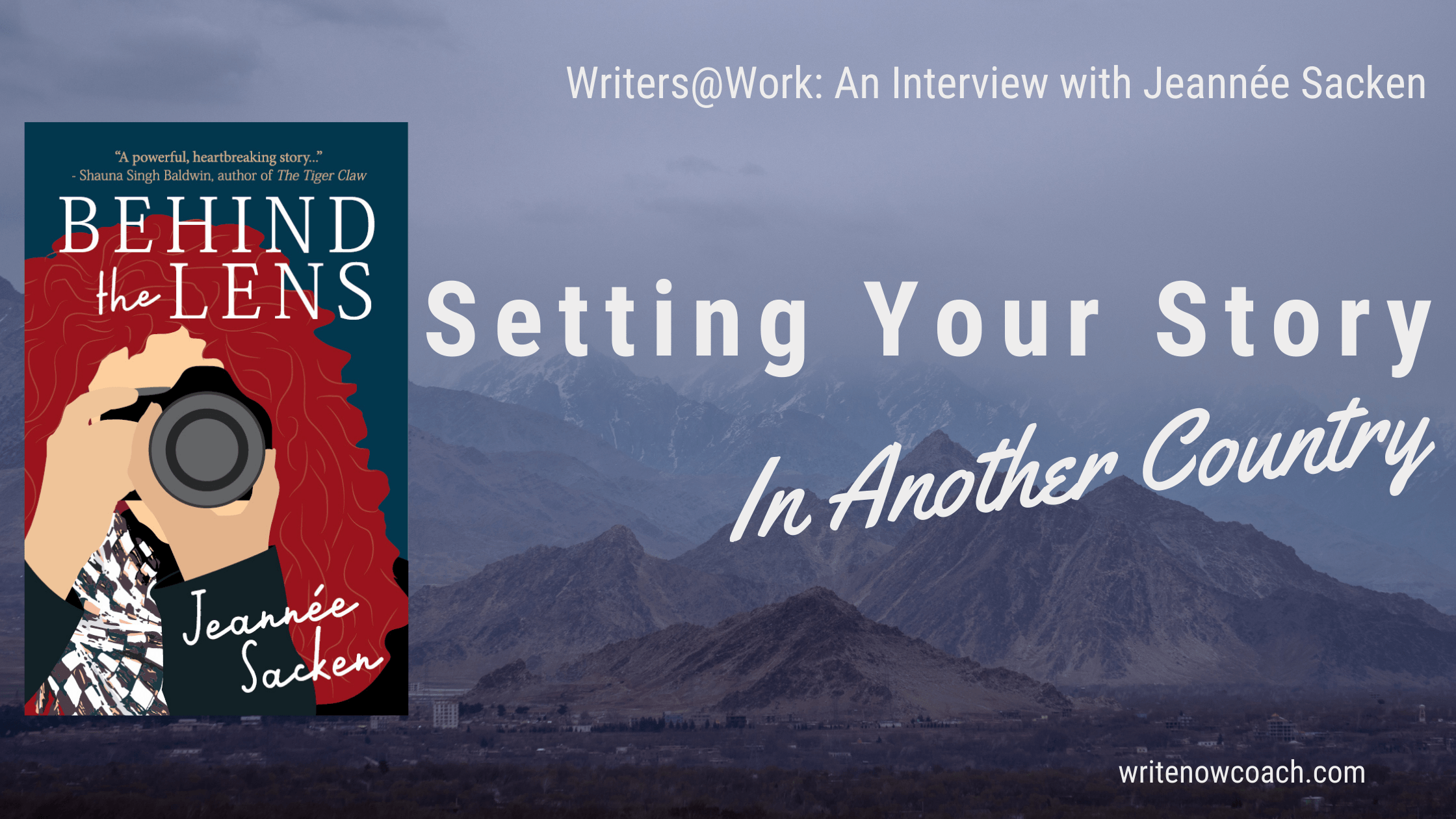

Today, I’m delighted to welcome my longtime friend and colleague Jeannée Sacken to the blog. I’m beyond thrilled to share with you our interview about her brand new book, Behind the Lens.

![]() And if you want to know even more about Jeannée and her work, we’ll be in conversation on Tuesday, March 23 at a virtual event hosted by Boswell Book Company and sponsored by Shorewood Public Library.

And if you want to know even more about Jeannée and her work, we’ll be in conversation on Tuesday, March 23 at a virtual event hosted by Boswell Book Company and sponsored by Shorewood Public Library.

Enjoy!

Rochelle

Writers@Work:

Setting Your Story in Another Country

An Interview with Jeannée Sacken

Welcome to the blog, Jeannée! Tell us about your new book, Behind the Lens.

Behind the Lens is about Annie Hawkins Green, a seasoned war photographer, who barely survives a Taliban ambush that leaves her military escort dead and a young Afghan girl dying in her arms. Years later, she returns to Afghanistan to teach a photography workshop at the school for girls run by her expat best friend. As the Taliban regain prominence in the once peaceful Panjshir Valley, Annie’s nightmares from her last time in-country come roaring back with a vengeance.

At its heart, the story is about Annie’s struggle to atone for a photograph she took that she believes set in motion a series of tragic events. I also explore themes and relationships that intrigue me: friendships and how they endure despite years of separation; mothers’ relationships with their daughters when mothers have an all-consuming career they love; the impact of war on journalists; and the sometimes exploitative nature of photography—a photographer can become famous based on capturing another person’s image.

What inspired this story?

Honestly, once upon a time, this story had another life. I set the novel in Ciudad Juárez and created a protagonist who was a photographer working with a human rights organization to investigate the deaths of women working in factories. But it just didn’t work. The manuscript sat on a shelf for years. When I looked at it again, I realized that I still loved the main character: Annie Hawkins Green. But she needed to be a war photographer. For that, I needed a war zone. Enter Afghanistan, and it all came together. However, this is not a war novel. Conflict bookends the story and provides tension that runs throughout. But just like Annie documents the lives of civilians as they live with conflict going on around them, that’s what happens in this story.

I’ve heard people say, “Write what you know”—and as a photographer and traveler, I am sure you were able to use your experience to write Annie’s story. But how did you research the other parts of her story?

First, I need to say that although I am a photographer and have red hair, this is not my story. It’s most definitely Annie’s, and it is fiction. That said, I most definitely used some of my own experiences in this book and certainly as a photographer, I’ve captured some images that have made me worry about “stealing a soul.” But like Annie, if I ask and my subject says “no,” puts up her hand, or shakes her head, I walk away. As to research: I read works of nonfiction and novels set in Afghanistan including Khalid Husseini’s The Kite Runner and A Thousand Splendid Suns. They gave me a foundation.

I also researched every single aspect and detail of this book—a lot of it before I started writing, with additional research while I was drafting and revising. I learned early on that the internet is my friend—so long as I double and triple check everything. I found recipes and maps, YouTube videos of traditional Afghan dances and a driving trip along the River Road up to my fictional village of Wad Qol. You name it.

Some of my research came from interviews. I am fortunate that my brother is a former U.S. Naval officer, and he provided enormous help, although a lot of those parts ended up on the cutting room floor. Of utmost importance to me was getting the Islamic aspects of the story right. To that end, I met with members of Masjid Al-Huda of South Milwaukee while I was drafting. Later, I made contact with the Muslim Public Advisory Counsel, and they put me in touch with the incomparable Heba Elkobaitry, a Muslim cultural and sensitivity reader. She was working on a documentary about 9/11 for the History Channel but made time to read my manuscript and made invaluable corrections and suggestions.

Did your research uncover anything that surprised you?

There were two things I ran across during my research that proved so compelling I knew they had to be in the story. First and foremost, the education (really, the lack thereof) of girls in Afghanistan, and not just in the time of the Taliban. Second, landays, 22-syllable poems, composed by Pashtun women for hundreds of years. This was and remains a largely oral tradition because women and girls weren’t allowed to learn to read or write and women writing poetry is still considered a violation of family honor. The word landay, I learned is also the Pashtun word for a particularly venomous snake. Similarly, these poems are sharp and sometimes deadly lines about love and death, war and separation. Once I discovered the poems and found two transcribed and translated anthologies, I knew they needed to feature prominently in the novel.

I really admire the way you were able to write a story that moved between Annie and her personal relationships and the dangers she faces in Afghanistan. What tools or techniques do you use to help with pacing?

I really appreciate stories that shift between different points in time or place or among various characters. Julia Alvarez, Michael Ondaatje, and Cristina Garcia all do this brilliantly. Building tension also requires a kind of shifting as well as attention to pacing. When a soldier or a journalist or a civilian is in a conflict zone, it’s not all battle scenes. I juxtapose moments of peace and serenity with moments of violence—like when Annie is at the Dalan Sang checkpoint. Just when she thinks she’s safe, danger strikes.

Another technique I use depends on the reader coming along for the ride. The chase and the anticipation of what could happen are often scarier than the tragic outcome. In a war zone, people are often just going about their lives, but always underneath they’re imagining the horror that could happen, that likely will happen. To capture that, I do a few things. When Annie first returns to Afghanistan, she’s aware of the potential danger, but all is peaceful, so she feels safe. Gradually, she remembers her last time in-country, and nightmares start to haunt her, leaving her and the reader wondering what’s really happening and what’s in Annie’s head. And since this book is written from Annie’s perspective, we’re always in her head. In the midst of all this conflict and danger, I needed Annie to have some normal moments away from it all. So, as she and Cerelli, the U.S. Naval officer who saved her life, fall in love, it’s over a series of satellite phone calls. Each call has its own short chapter building another sort of tension throughout the novel.

What are you reading now?

Time to confess. I don’t read when I’m drafting, and right now I’m working on the third book in the Annie Hawkins Green series. But if I were reading, the book on the top of the pile towering next to my bed is Send for Me by Lauren Fox. Right underneath is Ann Cleeves’ Wild Fire and Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell.

A former English professor, Jeannée Sacken is a photojournalist who travels the world documenting the lives of women and children. She lives in Shorewood, Wisconsin with her husband and cat, where she’s hard at work on her next novel also featuring Annie Hawkins Green. Follow Jeannée at jeanneesacken.com.