Writers Read: The Stories that Don’t Make Sense by Jocelyn Koehler

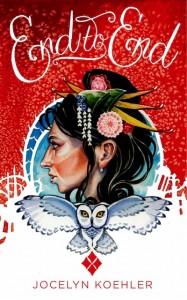

Our Friday Writers Read posts give authors an opportunity to write about the books that inspire their work. Today, Jocelyn Koehler writes about the enigmatic and engaging world of fairy tales—contemplating how we make sense of the stories that don’t make sense. Jocelyn will also be one of the guests at our June Write Now! Mastermind class. She’ll bring her experience as an author, editor, and publisher to talk about: From Premise to Published: How to get your book from first draft to first sale. If you’re not already a member of the Write Now! Mastermind class, you can sign up here. And don’t forget to enter the contest to win an electronic copy of Jocelyn Koehler’s new book End to End.

Writers Read: The Stories that Don’t Make Sense by Jocelyn Koehler

Writers Read: The Stories that Don’t Make Sense by Jocelyn Koehler

When I was young, I devoured fairy tales. I started with the easy ones (in which Mickey Mouse often played the role of the hero), but soon moved onto the more nuanced tales of the Grimms, Andersen, and Perrault. I’d also pick up folktale anthologies whenever I saw them.

So I had a lot of stories in my stack. Some, like Cinderella, had a simple and undeniable appeal: good girl, fancy party, happy ending. Easy! Other tales were not so digestible. One of the trickiest tales for me was the Scottish legend Tam Lin, whether as a poem or prose. It was so clearly a love story, yet I hated the suggestion of rape that so many versions contained:

He took her by the milk-white hand,

And by the grass green sleeve,

And laid her low down on the flowers,

At her he asked no leave.

As an impressionable young reader, that detail jumped out at me, and rendered the rest of the story difficult. If Tam Lin seduced Janet, why would she be willing to risk her life for him? Clearly, something was missing. In the centuries since the first telling and the last, someone had made a big mistake.

Things like this were one reason fairy tales became a bit of an obsession for me. I packed my shelves with books that offered new versions or ways to explain the psychology at work in such stories. Here are a few of them:

Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm by Philip Pullman

Pullman gathered fifty of the original 200+ tales and carefully honed them into tidier shapes. In other words, he acts as editor as much as a writer here. Anyone who has read the originals will recognize these versions. His sometimes tart commentary shows up in the notes following each tale. A writer could study these tales to understand how the structure and wording can be worked to be tight and flat as well, a fairy tale. And the book can certainly be used as an introduction and jumping off point for those who really want to dig into folktales and mythologies.

Changing Woman and Her Sisters: Stories of Goddesses from Around the World by Trina Schart Hyman & Katrin Hyman Tchana

This is a lavish picture book featuring stories of goddesses in ten different cultures. In addition to the lovely, haunting illustrations, the stories show just how much common ground folktales share, no matter where they come from. Brave daughters, young lovers, vengeful spirits, and divine inspiration can be found anywhere.

My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me: Forty New Fairy Tales edited by Kate Bernheimer.

In this anthology, some big name modern writers offer their own versions of fairy tales, which are almost always darker and often more frightening than the originals. It’s in collections like this one that readers realize how close to horror a lot of folktales can be. But at the same time, the new interpretations can often illuminate a meaning perfectly, in a way that makes you say, “Oh, of course that’s what that means! Why didn’t I see it before?”

After reading many of these types of books, I got a better sense of how I could read the difficult tales like Tam Lin, shedding the historical skin of the story to get at the heart of the narrative. In an effort to explain to myself how the story might work, I rewrote it entirely, changing the setting to a fairytale world rather like Japan. I gave Tam Lin a better reason for his elusiveness, and gave my protagonist a new name (Pearl) as well as a more inward-facing quest. I don’t know if my version will work for all readers, but it certainly helped me reconcile some of my issues with the familiar legend.

Your turn: If you’re a writer, do you read or write your way out of problems? And as a reader, do you keep looking for the “right” story? And how do you know when you’ve found it?

About the author. Jocelyn Koehler writes science fiction and fantasy. Some of her creative fiction has appeared in places like Crossed Genres, Actionman Magazine, and BURST. Her longer fiction is published by Hammer & Birch. Her latest book is End to End, published in May 2013.

About the author. Jocelyn Koehler writes science fiction and fantasy. Some of her creative fiction has appeared in places like Crossed Genres, Actionman Magazine, and BURST. Her longer fiction is published by Hammer & Birch. Her latest book is End to End, published in May 2013.

Find Jocelyn Koehler online here:

Thank you for a new fairy tale to explore! Like you, I collect them. Like you, there are pieces that never “set well” with me. It seems that bits are missing or things have been slightly altered (as happens with oral history) and we are left with stories that resemble jigsaw puzzles bought at a yard sale.

My sons enjoyed fairy tales as much as my daughter, but it wasn’t until I was reading them to HER, that I realized that many have become morality tales for girls. I look forward to tearing apart the Tamlin myth to see what makes it tick!

Peg, I was just talking about this to a friend (we were also discussing the “pinked” covers that scare boys away from reading fairy tales). Too often, fairy tales get altered to send unhelpful messages to girls (and boys): stay in your tower till the prince shows up! Pick your wife based on shoe size! There are so many to choose from…sigh.